The Peter principle

Whether you know it by name or not, you’ve probably heard of the Peter principle. First appearing in Laurence J. Peter’s book The Peter Principle, it goes as follows: “in a hierarchy every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence.”

If you’ve spent any time in any organization, big or small, this aphorism likely rings true. Or just look around. Isn't it the case that almost every bureaucracy you’ve dealt with lately is filled with people ill-suited to their tasks? As Peter puts it: “the cream rises until it sours.”

The irony is that, if you were to read The Peter Principle, you’d notice that Peter was not offering management wisdom…it was satire! This was a send up of stuffy management books (e.g. according to Peter, one of the many hazards of ladder climbing was so-called “Tabulatory Gigantism” - an all-consuming obsession with having a bigger desk than one’s colleagues).

And yet, it turns out that the Peter principle may indeed be provably true.

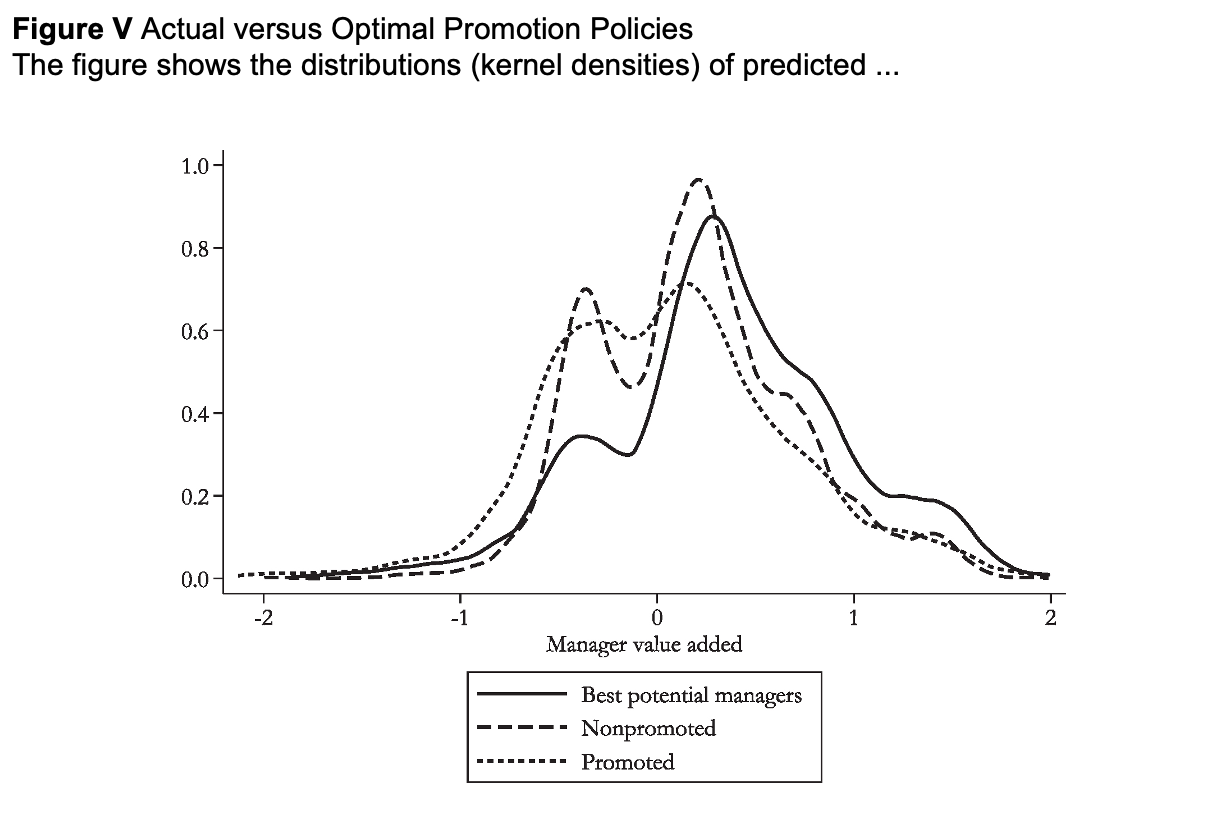

Authors Benson, Li and Shue found in their paper “Promotions and the Peter Principle” that firms promote based on past performance, not future potential, and are suffering as a result. In the paper, they were able to show that firms promote high-performing salespeople ahead of lower-performing salespeople with greater managerial potential, and they were able to estimate these suboptimal managers “decreased subordinate performance” by 30%.

To be clear, they’re quick to caveat this estimate. They do not mean to suggest “that firms would actually achieve a 30% gain in sales” by changing their promotion policy, as such a change could alter incentives in other ways that aren’t easy to model.

But still…that’s a pretty big result! If you could somehow boost sales by 30%, even 10%, just by changing your promotion policy, wouldn’t you do it?

One of the glorious things about working at an early stage startup is that the Peter principle is irrelevant. Everybody is either building or selling. And the team is small enough that no hierarchy is needed. You’re all on the same page simply by existing in the same room together.

But one thing I’ve noticed is that once a company raises a series A, founders suddenly want to grow up. And the most obvious way to grow up is to start adding hierarchy. And the most obvious way to add hierarchy is to promote your top performers.

The Peter principle strikes again.

This is the hierarchy trap that I’ve written about before. It’s hard to blame a massive organization for being slow to evolve, but startups should be able to plot a more optimal course given the data at hand. So if you’re starting to grow up, remember the Peter principle. Maybe even give that paper a read. And think carefully about how you promote and who you promote, because it turns out, there’s quite a bit of alpha in doing it well.